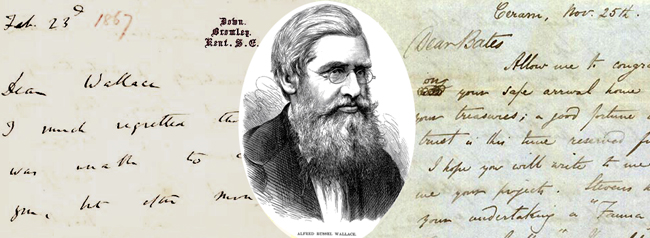

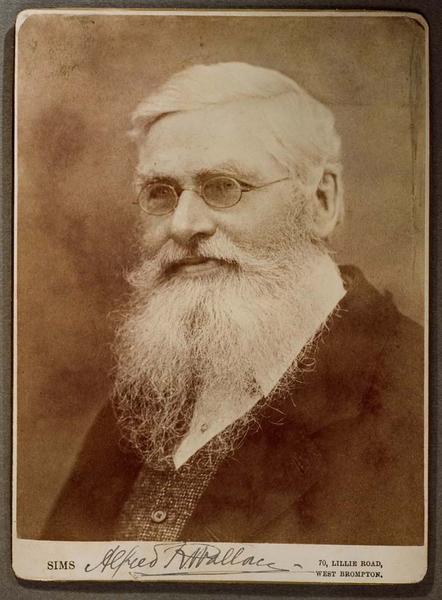

Alfred Russel Wallace OM, LLD, DCL, FRS, FLS (1823 - 1913), one of the greatest scientists of all time. His seminal contributions to biology rival those of his friend and colleague Charles Darwin, though he is far less well known. Together Wallace and Darwin proposed the theory of evolution by natural selection in 1858, and their prolific subsequent work laid the foundations of modern evolutionary biology - and much more besides.

Alfred Russel Wallace OM, LLD, DCL, FRS, FLS (1823 - 1913), one of the greatest scientists of all time. His seminal contributions to biology rival those of his friend and colleague Charles Darwin, though he is far less well known. Together Wallace and Darwin proposed the theory of evolution by natural selection in 1858, and their prolific subsequent work laid the foundations of modern evolutionary biology - and much more besides.

Wallace made enduring scholarly contributions to subjects as diverse as glaciology, land reform, anthropology, ethnography, epidemiology, and astrobiology. His pioneering work on evolutionary biogeography (the science that seeks to explain the geographical distribution of organisms) led to him becoming recognised as that subject’s ‘father’. Beyond this, Wallace is regarded as the pre-eminent collector and field biologist of tropical regions of the 19th century, and his book The Malay Archipelago (which was Joseph Conrad’s favourite bedside reading) is one of the most celebrated travel writings of that century and has never been out of print. Wallace was a man with an extraordinary breadth of interests who was actively engaged with many of the big questions and important issues of his day. He was anti-slavery, anti-eugenics, anti-vivisection, anti-militarism, anti-Imperialism, a conservationist and an advocate of woman's rights. He strongly believed in the rights of the ordinary person, was a socialist, a proponent of land nationalisation, and an anti-vaccinationist (for rational reasons). A materialist until his 40s, he gradually developed a belief in naturalistic, evolutionary spiritualism.

During Wallace's lifetime he was widely credited as being the co-discoverer of the process of evolution by natural selection and he was duly honoured for his role in its discovery by being awarded the Darwin–Wallace and Linnean Gold Medals of the Linnean Society of London; the Copley, Darwin and Royal Medals of the Royal Society (Britain's premier scientific body); and the Order of Merit (awarded by the ruling Monarch as the highest civilian honour of Great Britain). Wallace was highly regarded by his contemporaries and he met and corresponded with many of the leading figures in science, politics and literature both in Europe and North America. During his ten month lecture tour of the United States of America and Canada in 1886 and 1887, his company was sought by the principal scientists and writers of the day, and President Cleveland himself gave Wallace a tour of the White House.

During Wallace's lifetime he was widely credited as being the co-discoverer of the process of evolution by natural selection and he was duly honoured for his role in its discovery by being awarded the Darwin–Wallace and Linnean Gold Medals of the Linnean Society of London; the Copley, Darwin and Royal Medals of the Royal Society (Britain's premier scientific body); and the Order of Merit (awarded by the ruling Monarch as the highest civilian honour of Great Britain). Wallace was highly regarded by his contemporaries and he met and corresponded with many of the leading figures in science, politics and literature both in Europe and North America. During his ten month lecture tour of the United States of America and Canada in 1886 and 1887, his company was sought by the principal scientists and writers of the day, and President Cleveland himself gave Wallace a tour of the White House.

By the time of his death in 1913 Wallace was the world’s most famous contemporary scientist. Large numbers of obituary notices appeared in newspapers and other publications worldwide which paid tribute to him. The Daily Mirror (London) commented on 8 November 1913 that “Science has lost its 'grand old man' Dr. Alfred Russel Wallace, the greatest of all modern scientists - co-originator with Charles Darwin of the theory of natural selection - died yesterday at his home..." Current Opinion (New York) summed up these tributes in January 1914 by stating that "Only a great ruler could have been accorded by the press of the world any such elaborate obituary recognition as was evoked by the death of Alfred Russel Wallace..."

After Wallace's death his intellectual legacy was soon overshadowed by Darwin’s for a variety of complex reasons and this remained the case for many decades. In recent years, however, interest in Wallace has been steadily increasing, as indicated, for example, by the fact that about fourteen biographies have appeared since the year 2000 - more than doubling the number published since his death. Wallace is now becoming the focal point for researches in a range of disciplines, but work on him is often frustrated by the difficulty of obtaining digital copies or transcripts of his correspondence and other manuscripts. His letters in particular, contain much key information absent from his published works; ranging from previously unpublished facts about his life, to details about the development of his many important scientific theories. A list of his correspondents reads like a “who’s who” of 19th century science and society and includes Charles Darwin,  Thomas Henry Huxley, Charles Lyell, Joseph Dalton Hooker, Henry Walter Bates, Richard Spruce, Francis Galton, Sir William Thiselton-Dyer, William Henry Fox Talbot, Herbert Spencer, Charles Kingsley, Lord Morley and Gertrude Jekyll, amongst others. Unfortunately however, Wallace's correspondence and other manuscripts are scattered amongst the libraries of c. 250 institutions in several countries and only a very small proportion of these documents have ever been published. Most of the letters which have been are contained in Wallace's 1905 autobiography My Life; A Record of Events and Opinions and Marchant's 1916 book Alfred Russel Wallace; Letters and Reminiscences, but unfortunately these transcripts contain many errors and even important omissions of text.

Thomas Henry Huxley, Charles Lyell, Joseph Dalton Hooker, Henry Walter Bates, Richard Spruce, Francis Galton, Sir William Thiselton-Dyer, William Henry Fox Talbot, Herbert Spencer, Charles Kingsley, Lord Morley and Gertrude Jekyll, amongst others. Unfortunately however, Wallace's correspondence and other manuscripts are scattered amongst the libraries of c. 250 institutions in several countries and only a very small proportion of these documents have ever been published. Most of the letters which have been are contained in Wallace's 1905 autobiography My Life; A Record of Events and Opinions and Marchant's 1916 book Alfred Russel Wallace; Letters and Reminiscences, but unfortunately these transcripts contain many errors and even important omissions of text.

What is needed then, is for digital copies of all of Wallace's manuscripts to be gathered together into a single archive, and for transcripts of these documents to be made available to scholars via the Internet, and in printed form. This is exactly what the Wallace Correspondence Project aims to do. Note that electronic images of all of Wallace's correspondence and other manuscripts can not be made publically available for a number of reasons (mainly IPR related), so transcripts have to be relied on instead. Since most users will not have access to the original documents and therefore cannot compared the transcripts to them, every effort has to be made to make the transcripts as accurate as possible.

Collating Wallace’s manuscripts, transcribing and publishing them, in both a series of printed volumes and via a freely accessible online archive, will mark a huge advance in Wallace studies which is likely to generate a surge of scholarly work on all aspects of his life and work. It will be an important resource for students of the history of science, cultural studies and 19th century society, and for scholars interested in that generation of scientists who were at the centre of the debate on evolution. For many of these scientists the theory of natural selection raised major contradictions in their own systems of belief. Access to the correspondence between those responsible for initiating the debate would advance the understanding of the history of the debate, while revealing some of the personal conflicts that individuals experienced.