This letter (WCP349) was written in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

"I am afraid the ship’s on fire."

These fateful words were uttered by the Captain of the Brig Helen on 6 August 1852, which was sailing from South America to London, as a fire broke out in the ship’s hold. The dramatic events of the fire and subsequent rescue of the ship’s crew and passengers are recorded in a letter from Wallace, who had spent the previous four years travelling through the Amazon, to his friend Richard Spruce (1817-1893).

WCP349: Page one of the eight page letter to Spuce detailing the sinking.

The letter was written from the Brig Jordeson on 19 September 1852, the vessel that saved the stricken survivors after they had endured ten harrowing days and nights in a small row boat, 200 miles from the nearest land, with water seeping into the boat from numerous holes. Wallace describes how he was “scorched by the sun, [his] hands nose and ears being completely skinned, and [was] drenched every day by the seas and spray”. They finally anchored ship at Deal, Kent, on 1st October with Wallace rejoicing to Spruce

“Oh! Glorious day! Here we are on shore at Deal where the ship is at anchor. Such a dinner! Oh! Beef steaks and damson tart, a paradise for hungry sinners.”

The joy at being back on dry land in England is clear to see, made even more poignant by the terrible storms they had to endure in the English Channel the night before they anchored; storms, in which “many vessels were lost”.

Wallace’s journey to the Amazon began in Leicester in 1844 when he met budding young amateur naturalist Henry Walter Bates (1825-1892), after Wallace accepted a job at the Collegiate School there. Wallace moved to Neath, Wales in 1845, but kept in regular contact with Bates, and it was this friendship that first stirred in Wallace an interest in entomology.

A seed was sown in Wallace’s mind after reading William Henry Edwards' book A Voyage up the River Amazon, and early in 1848 he began making plans with Bates for their own voyage to South America. This idea came to fruition as the two young, eager friends set sail from Liverpool on 26 April 1848 bound for Pará (Belém).

For Wallace the aim of their Amazon trip was two-fold. Firstly, they were to go and collect specimens of birds, insects and other animals not only for their private collections, but also to sell to collectors and museums across Europe. Secondly, Wallace went with the aim of attempting to discover the mechanism of evolution. Having read the controversial Vestiges of Natural History of Creation by Robert Chambers in 1845, he became convinced of the reality of evolution, which was then known by the term of transmutation. Indeed, in a letter to Bates in 1847, he asserted that he sought to “take one family, to study thoroughly- principally with a view to the theory of the origin of species”.

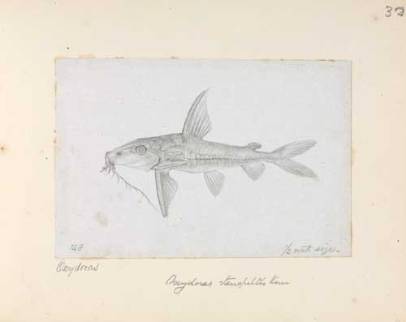

Wallace and Bates parted company whilst there to focus on different areas, with Wallace travelling around the Amazon basin and Rio Negro. It was here he made beautifully intricate drawings of fish species he found on the Rio Negro, and also used his land surveying skills to create a wonderfully detailed map of the Rio Negro; so detailed and accurate that it became the standard map of the river for many years.

Wallace decided to leave the Amazon in 1852 after becoming quite poorly. He sadly lost his brother, Edward, in June 1851 to yellow fever, after Edward had joined Wallace and Bates earlier on the expedition. Wallace boarded the Brig Helen on 12 July, sailing for 26 days before disaster struck.

Wallace describes very candidly in his letter to Spruce the frantic moments after the discovery of the fire and the realisation that they would need to abandon ship. He managed to run back to his cabin and collect some items together in a small tin box. He tells Spruce he felt “foolish” in saving his watch and money. However, once aboard the life-boat his regrets at not having “saved some new shoes, cloth coat and trousers” are clear to see.

Tragically, Wallace lost all of his natural history specimens, so painstakingly collected over the previous two years; the specimens he collected during the first two years having been successfully posted back to his agent, and he recounts this tragedy to Spruce in the letter:

“My collections however were in the hold and were irrevocably lost. And now I begin to think, that almost all the reward of my four years of privation and danger were lost. What I had hitherto sent home had little more than paid my expenses and what I had in the “Helen” I calculated would realise near £500 [around £30,000 in today’s money]. But even all this might have gone with little regret had not far the richest part of my own private collection gone also. All my private collection of insects and birds since I left Pará was with me, and contained hundreds of new and beautiful species which would have rendered (I had fondly hoped) my cabinet, as far regards American species, one of the finest in Europe”

A few gems from this trip, however, do survive, and are preserved by us here at the Museum, the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and The Linnean Society. When in his cabin, frantically trying to fit as much as he could in his tin box, Wallace scooped up the drawings he had made of the fishes of the Rio Negro and of Amazonian palms. The Library’s Special Collections now hold the four volumes of fish drawings, with the palm drawings held by the Linnean. The specimens of palms collected, which are now housed in Kew’s Herbarium, were sent back during the first two years of the expedition.

One of Wallace's fish drawings that we hold here at the Museum

At the end of his letter to Spruce, written from London on 8 October, Wallace muses about his next trip. He mentions the Andes or the Philippines as possible destinations for his next collecting expedition.

However, as we know, in 1854, Wallace headed out to explore the islands of the Malay Archipelago (Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and East Timor), spending eight years there.

This letter of the month highlights the real danger faced by those who travelled to far flung corners of the world in the hope of advancing our understanding of the natural world, in sometimes dangerous and harsh conditions. It’s hard not to feel for Wallace having lost the fruits of his hard fought labour.

However, every story has a silver lining and Wallace’s Malay Archipelago trip certainly must have helped heal the wounds of the lost Amazon collections. The result of eight years hard work in south-east Asia was an unrivalled collection of 110,000 insects, 7,500 shells, 8,050 bird skins, and 410 mammal and reptile specimens, including well over a thousand species new to science. His book The Malay Archipelago, first published in 1869, is the most celebrated travel book of that region and has not been out of print since it was first published.

-Caroline-