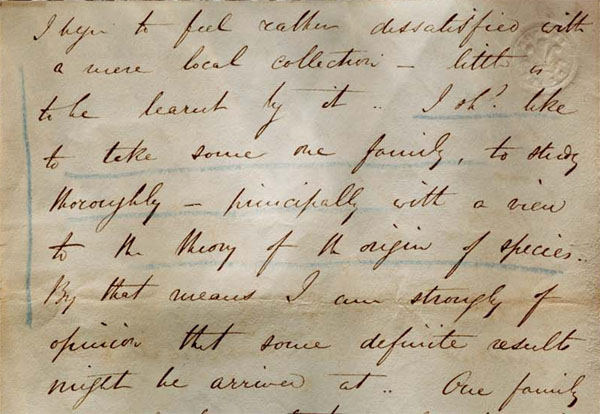

Alfred Russel Wallace was born near Usk, Monmouthshire, England (now part of Wales) on the 8th of January 1823 to a downwardly mobile middle-class English couple. Due to his father's deteriorating financial situation he was forced to leave school aged 14 and work for his brother William doing land surveying. This job involved roaming all over the English and Welsh countryside and it was at this time that his strong interest in natural history developed. Wallace became an evolutionist in 1845 whilst living in Neath in Wales, after being inspired by Robert Chambers' controversial book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. So interested in the subject did he become that in 1848 he suggested to his friend Henry Walter Bates that they go on an expedition to the Amazon rainforest in Brazil to collect and study animals and plants and try to solve the great "mystery of mysteries" of how evolutionary change has taken place. Although Wallace made many important discoveries during his four years in the Amazon Basin he did not manage to find the elusive mechanism. That would have to wait until some time later.

Alfred Russel Wallace was born near Usk, Monmouthshire, England (now part of Wales) on the 8th of January 1823 to a downwardly mobile middle-class English couple. Due to his father's deteriorating financial situation he was forced to leave school aged 14 and work for his brother William doing land surveying. This job involved roaming all over the English and Welsh countryside and it was at this time that his strong interest in natural history developed. Wallace became an evolutionist in 1845 whilst living in Neath in Wales, after being inspired by Robert Chambers' controversial book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. So interested in the subject did he become that in 1848 he suggested to his friend Henry Walter Bates that they go on an expedition to the Amazon rainforest in Brazil to collect and study animals and plants and try to solve the great "mystery of mysteries" of how evolutionary change has taken place. Although Wallace made many important discoveries during his four years in the Amazon Basin he did not manage to find the elusive mechanism. That would have to wait until some time later.

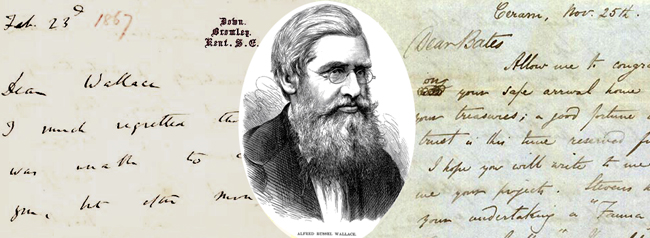

Part of an 1847 letter from Wallace to Bates.

Copyright Wallace Family, The Natural History Museum & Fred Langford Edwards

Wallace returned to England in October 1852, after surviving a disastrous ship wreck in which most of the thousands of natural history specimens he had laboriously collected in the Amazon were destroyed. Undaunted he soon started to plan his next trip and in 1854 he set off for the Malay Archipelago (now Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia) where he would spend nearly eight years travelling, collecting and writing. He visited every important island in the archipelago at least once, and several on multiple occasions, and collected almost 110,000 insects, 7500 shells, 8050 bird skins, and 410 mammal and reptile specimens, including over a thousand species new to science.

In February 1855 whilst in Sarawak, Borneo, Wallace wrote what was probably the most important paper published on evolution up until that point. His "Sarawak Law" article made such an impression on the famous geologist Charles Lyell that in November 1855, soon after reading it, Lyell started writing a "species notebook" in which he began to contemplate the idea of evolutionary change. In April 1856 Lyell paid a visit to Darwin at Down House, and Darwin divulged his theory of natural selection to Lyell for the first time: an idea which Darwin had been working on, more or less in secret, for about 20 years. Soon afterwards Lyell sent a letter to Darwin urging him to publish the theory lest someone beat him to it (he probably had Wallace in mind!), so in May 1856 Darwin, heeding this advice, began to write a "sketch" of his ideas for publication. Finding the "sketch" unsatisfactory, Darwin abandoned it in about October 1856 and instead began to write an extensive book on the subject.

In February 1855 whilst in Sarawak, Borneo, Wallace wrote what was probably the most important paper published on evolution up until that point. His "Sarawak Law" article made such an impression on the famous geologist Charles Lyell that in November 1855, soon after reading it, Lyell started writing a "species notebook" in which he began to contemplate the idea of evolutionary change. In April 1856 Lyell paid a visit to Darwin at Down House, and Darwin divulged his theory of natural selection to Lyell for the first time: an idea which Darwin had been working on, more or less in secret, for about 20 years. Soon afterwards Lyell sent a letter to Darwin urging him to publish the theory lest someone beat him to it (he probably had Wallace in mind!), so in May 1856 Darwin, heeding this advice, began to write a "sketch" of his ideas for publication. Finding the "sketch" unsatisfactory, Darwin abandoned it in about October 1856 and instead began to write an extensive book on the subject.

In February 1858 Wallace was suffering from an attack of fever on the remote Indonesian island of Gilolo (Halmahera) when suddenly the idea of natural selection occurred to him. As soon as he had sufficient strength he wrote an detailed essay explaining his theory and sent it together with a covering letter to Darwin, who he knew from correspondence was interested in the subject of species transmutation (as evolution was then called). He asked Darwin to pass the essay on to Lyell if Darwin thought it was sufficiently interesting - evidently hoping that Lyell would ensure that it was published in a good journal. Lyell (who Wallace had never been in contact with) was one of the most respected scientists of the time and Wallace must have thought that he would be interested to learn about his new theory because it explained the evolutionary "law" which Wallace had proposed in his 1855 paper. Darwin had mentioned in a letter to Wallace that Lyell had found his "Sarawak Law" paper noteworthy.

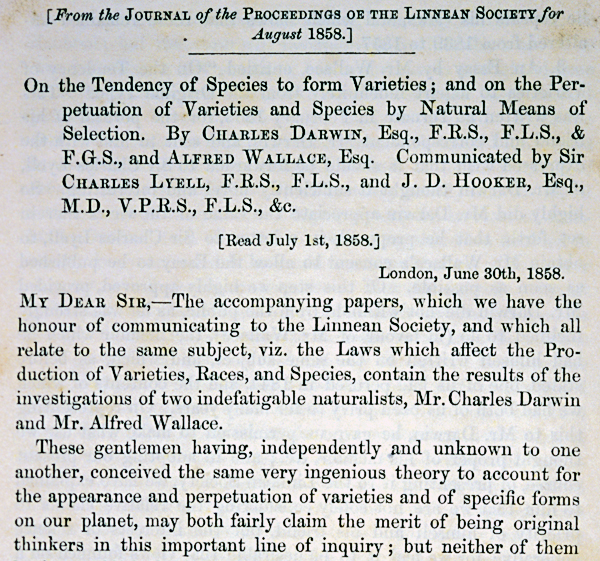

Unbeknownst to Wallace, Darwin had discovered natural selection many years earlier. He was therefore horrified when he received Wallace's letter and immediately appealed to his friends Lyell and Joseph Hooker for advice on what to do. They famously decided to present Wallace's essay (without first asking his permission!), along with two unpublished excerpts from Darwin's writings on the subject, to a meeting of the Linnean Society of London on July 1st 1858. These documents were published together in the Society's journal a month later as the paper "On the Tendency of Species to Form Varieties; And On the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection". Darwin's contributions were placed before Wallace's essay, thus emphasising Darwin's priority to the idea. Wallace later grumbled that his essay "...was printed without my knowledge, and of course without any correction of proofs", contradicting Lyell and Hooker's statement in their introduction to the joint papers that "...both authors...[have]...unreservedly placed their papers in our hands". This unfortunate episode prompted Darwin to abandon writing his big book on evolution and instead, he rushed to produce an "abstract" of what he had written up until that point. This "abstract" was published fifteen months later in November 1859 as On the Origin of Species: a book which Wallace once remarked would "...live as long as the 'Principia' of Newton."

Unbeknownst to Wallace, Darwin had discovered natural selection many years earlier. He was therefore horrified when he received Wallace's letter and immediately appealed to his friends Lyell and Joseph Hooker for advice on what to do. They famously decided to present Wallace's essay (without first asking his permission!), along with two unpublished excerpts from Darwin's writings on the subject, to a meeting of the Linnean Society of London on July 1st 1858. These documents were published together in the Society's journal a month later as the paper "On the Tendency of Species to Form Varieties; And On the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection". Darwin's contributions were placed before Wallace's essay, thus emphasising Darwin's priority to the idea. Wallace later grumbled that his essay "...was printed without my knowledge, and of course without any correction of proofs", contradicting Lyell and Hooker's statement in their introduction to the joint papers that "...both authors...[have]...unreservedly placed their papers in our hands". This unfortunate episode prompted Darwin to abandon writing his big book on evolution and instead, he rushed to produce an "abstract" of what he had written up until that point. This "abstract" was published fifteen months later in November 1859 as On the Origin of Species: a book which Wallace once remarked would "...live as long as the 'Principia' of Newton."

In spite of the theory's traumatic birth Darwin and Wallace developed a genuine admiration and respect for one another. Wallace frequently stressed that Darwin had more claim to the idea of natural selection than he did and he even named one of his most popular books Darwinism!

Wallace spent the rest of his long life explaining, developing and defending the theory of natural selection, as well as working on a very wide variety of other (sometimes controversial!) subjects. He wrote more than 800 articles and 22 books, the best known being The Malay Archipelago, The Geographical Distribution of Animals, and Darwinism. By the turn of the century he was very probably Britain's best known naturalist and by the time of his death in 1913, he may well have been one of the world's most famous people.

So why then was Wallace's intellectual legacy overshadowed by Darwin's? This is a tricky question, because the explanation has to take into account that during Wallace's lifetime he was widely acknowledged to be the co-discoverer of natural selection. The reason may be as follows: In the late 19th and early 20th century natural selection as an explanation for evolutionary change became very unpopular, with most biologists adopting alternative theories such as neo-Lamarckism, orthogenesis, or the mutation theory. It was only with the modern evolutionary synthesis of the 1930s and 1940s that natural selection became the generally accepted mechanism of evolutionary change. By then, however, the history of the discovery had been forgotten by many (there was a new generation of biologists) and when interest in the theory revived, many wrongly assumed that the idea had first been published in Darwin's On the Origin of Species. Thanks to the 'Darwin Industry' of recent decades, Darwin's fame has risen exponentially, eclipsing the important contributions of his contemporaries, like Wallace. The Wallace Correspondence Project hopes to help redress this imbalance.