EXPLORING THE LIFE OF ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE’S BROTHER-IN-LAW, THOMAS SIMS, ON THE 200th ANNIVERSARY OF HIS BIRTH (26 MARCH 2024).

By Anne Woodward (March 2024)

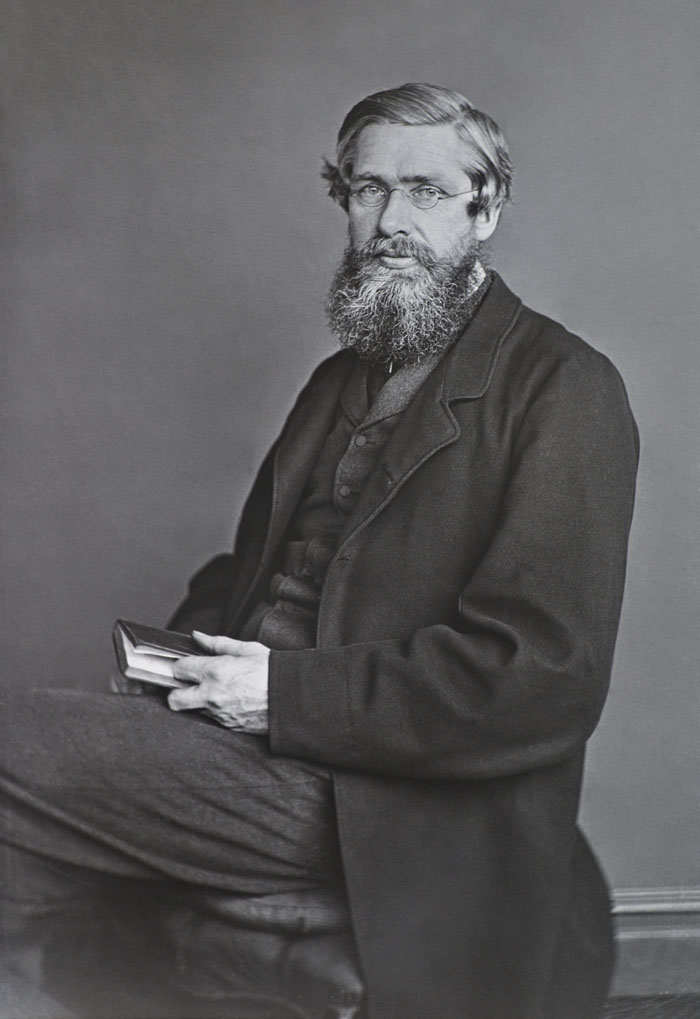

Daguerreotype portrait of Thomas Sims as a young man. (Ref: 1936.01.6)

Thomas Sims (1824-1910) was an early professional photographer and an active experimenter and inventor. He was the husband of Frances, the sister of Alfred Russel Wallace. As 2024 marks the bicentenary of his birth, this post looks back at his photographic career and, in particular, the valuable insight letters from the Wallace Correspondence Project (WCP) reveal about his home and business life.

The Thomas Sims collection – held by The Amelia Scott (formerly Tunbridge Wells Museum and Art Gallery) – is a treasure trove of notebooks, letters, documents, photographic images and equipment. In particular his unpublished memoir, written in later life, offers a fascinating insight into the early years of his photographic career. But there are tantalising omissions in Sims’s account, for example there is very little detail about his studios. Official and commercial records – including Census returns, trade directories and newspaper ads – have filled some gaps, but it is the letters published by the WCP that add context and bring his story to life. Only a selection of the letters are used here.

All the images used in this post are © Tunbridge Wells Borough Council t/a The Amelia Scott, except where noted. Unless otherwise stated, the post is based on research conducted using The Thomas Sims collection held by The Amelia Scott.

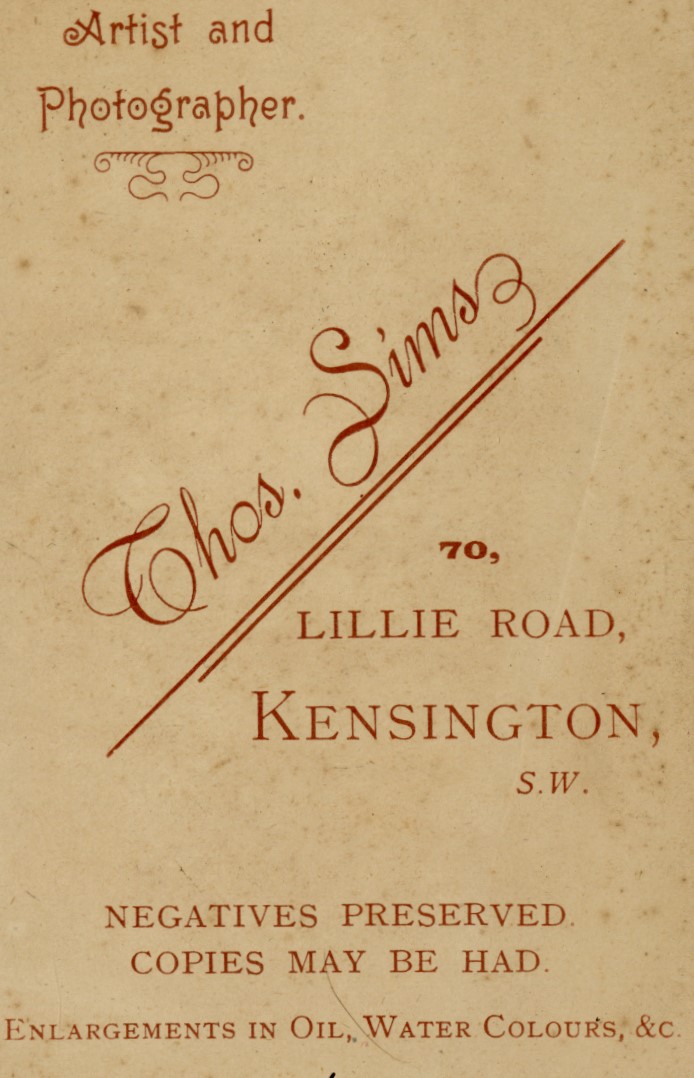

Wallace by Sims in 1869. The original is an ambrotype.

Copyright G. Beccaloni

Throughout his life Thomas Sims was encouraged and supported by his friend Wallace and in return Sims provided photographic illustrations for some of Wallace’s scientific works, as well as portraits of him (those which survive can be seen HERE). But before we turn to the letters here’s some biographical information about Thomas Sims.

Early Life

Thomas Sims was born on 26 March 1824 to Thomas and Sarah Sims of Goat Street, Swansea. Thomas Sims Snr was a cordwainer in Neath and his son Thomas Jnr also became a shoemaker. By 1845 the Sims family was taking in lodgers including Wallace and a friendship grew between the two families. This led to the marriage of Thomas Jnr to Frances "Fanny" Wallace on 15 February 1849 while Thomas was still a shoemaker.

Thomas Sims’s fascination with photography began in his home town. The first commercial studio in Wales was probably situated nearby in the grounds of the Royal Institution of South Wales (RISW - now Swansea Museum) in July 1842. Sims would no doubt have been aware of the RISW’s activities and its two Art Exhibitions of 1841 and 1842 that included photography. Sims would himself go on to have a temporary studio in the gardens of the RISW in 1851, although in his memoir he would remember it as "The Natural History Museum".

By 1847 Sims was experimenting with photography while still a shoemaker. He pointed out that there was very little practical knowledge to be had at the time and that progress could only be made through practical experimentation based on a sound knowledge of chemistry and optics.

He made his first camera using the wood of cigar boxes and a small meniscus lens and obtained his first negative image on 20 September 1847. In the same year Wallace brought back a whole-plate daguerreotype camera, from a trip to Paris with his siblings Fanny and John, to which Sims would later say he literally became a slave for many years.

In 1848 Sims attended the 18th Annual Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Swansea; a gathering of some of the leading figures in science. In his memoir he reports having a conversation with the scientist Robert Hunt, an influential early photographic pioneer, as well as listening to a paper by the photographer Antoine Claudet on the comparative values of bromine and chlorine vapour in the daguerreotype process.

In 1849 Thomas and Fanny Sims left Wales to start a photographic venture in Weston-Super-Mare.

Sims in Business

After his marriage to Fanny, the couple moved to Weston-Super-Mare and Sims (then in his mid-twenties) set up a daguerreotype studio at home on the veranda of Albert House. One gets the impression that Sims could be quite charming, his memoir is certainly very engaging. The first few years of business were not a commercial success and Fanny supplemented the family income by giving lessons in music, drawing and French. Her brother Herbert , writing from Brazil in September 1849, speculated that Fanny’s business would do well and hoped that Thomas would “…put a good face on the matter…” (WCP393). Fanny would continue to work throughout her life to supplement their income. A move back to Swansea in 1851 didn’t improve trade and by the autumn of 1852 we learn in a letter from John Wallace to his mother, that Thomas and Fanny were “undetermined about their future operations” (WCP1635).

Wallace’s return from South America gave Sims a much-needed lifeline. Wallace rented 44 Upper Albany Street in London at the end of 1852 and the couple moved in with Wallace and his mother Mary Ann. This was a good career move for Thomas, a London studio in a fashionable part of town offered excellent prospects. Within a year Sims had exhibited at the UK’s first major photographic exhibition – Recent Specimens of Photography, Society of Arts, London. 22 Dec 1852 to 29 Jan 1853 – where he exhibited 22 collodion photographs and also contributed a paper for the catalogue based on his experiments with collodion, “Collodion positives on glass”. His fellow exhibitors included major photographers of the day such as, William Henry Fox Talbot, Roger Fenton and Philip Henry Delamotte (who also submitted a paper). Sims’s inclusion in the exhibition, and the acceptance of his paper, must have boosted his confidence. He went on to produce a paper “On Engraving Photographs on Glass and Porcelain by means of Hydro-fluoric Acid Gas” for the Journal of the Photographic Society (21 January 1857); and in 1859 was granted GB patent 344 “Application of Photography to Engraving and Printing”. Perhaps he saw the need to protect his interests after his legal confrontation with W. H. F. Talbot.

Portrait on porcelain by Sims produced in June 1855 (Ref: 1936.01.12)

While Sims was living at 44 Upper Albany Street, he had two legal encounters with Talbot. The first in the spring of 1853 and the second abandoned by Talbot and settled in Sims’s favour in February 1855. The WCP unfortunately doesn’t cover the ensuing drama – and so it won’t be covered here – but the encounters scarred Sims who in later life became a vocal opponent of Talbot and his assertion of his photographic patent rights over photographers, which Sims felt siffled scientific experimentation.[1]

Despite his legal spat with Talbot, he was advertising his studio at no.44 in The Times (from June 1853) and was selling ambrotypes, “Photographic Portraits on Glass”, from 2s 6d each.

Sims gives few details about any of his studios but extracts from his memoir and WCP show that he kept servants and photographic employees and that he was aiming for an affluent clientele, rather than the working masses. In his memoir Sims recounts the below exchange with a servant, James, announcing the arrival of Mrs Nottage and her sister at 44 Upper Albany Street in 1853. Sims would go on to give Mrs Nottage photography lessons. According to Sims, she in turn taught her husband George Swan Nottage who would launch the London Stereoscope Co. in 1854.

“Well James any message? This was addressed to a model of a page we had at the time… “Yes Sir, please two beautiful young ladies want to sit for their portraits.” Tell them James I will wait upon them directly...”

Business appeared to go well, John Wallace writing to his mother in December 1853 noted he was happy to hear that “…Thomas and Fanny have plenty of work…” (WCP1288). But things changed in 1854 when a pattern of indecision and bad business moves crept in. Sims twice thought of moving abroad but was persuaded against it by John Wallace writing from California (WCP5576) and Wallace writing from Singapore (WCP354), on the grounds that photographic trade wouldn’t pay. Adverts started appearing in The Times again but by August Thomas had contracted cholera and was reported “much altered” by the experience (WCP5566 [not yet available online]).

There was an expensive, and arguably unnecessary, move to 7 Conduit Street, just off Regent Street, in 1855 that Wallace strongly advised against (WCP359). Wallace’s letter to Fanny, written from Borneo Island in Sep 1855 (WCP360) offers a goldmine of information about the move. The whole house - taken for £200 a year - was praised by Fanny’s mother for the “unequalled magnificence” of their rooms “quite a palace of photography”. But not long after Sims again contemplated going abroad. Wallace's influence over Fanny and Thomas was clearly diminished by being overseas for eight years and his letters, requesting news of the business, were often met by silence:

“…I am afraid you have been telling my mother not to write about your affairs or she would never have said so little as she has done in the last two letters. But why should you mind what she says to me? You know I don't judge hastily or harshly, & make full allowance for everything.” (WCP360)

He asked questions such as how is business, how much are you taking each month? He offered sound advice on Sims’s business cards, newspaper ads, customers and revenue streams.

“I am very much pleased to hear that you are getting on so well & that Thomas has at last got into the transparent pictures. He has never told me yet whether there is any thing new, or whether they are the same as he tried when I was with you & which I always told him would be sure to succeed if he would stick to them a little. You have not told me what you know I should so much be interested to hear, what he is to have for them… An order like that should make his fortune. If he has taken them at less than 5s. each it is absurd. At that I suppose for a thousand he might make something handsome. For such an order he ought to clear £100 for a months work.” (WCP359)

Incredibly, the following year Thomas and Fanny rented a second “country” residence, in Hammersmith, for the sake of Fanny’s health and Thomas took on “country commissions” while still keeping on Conduit Street. They would run two properties for the next four years.[2] and build up debts. But perhaps Thomas’s health was also failing. In a letter of September 1856, from Mary Ann Wallace (Fanny’s mother) to John Wallace:

“I could not help fancying Mr. Sims would have liked to have been in John’s situation (the Father of a fine boy) but the time is too far gone to expect that now. There is an unsettledness about Thomas Sims at times which would be dissipated by the prattle of a little one. Fanny is an excellen[t] wife, and amuses and rouses him when he is in a “key too low”.” (WCP5579)

In April 1859 Wallace, writing from Ternate Island, complimented Thomas on a long letter he sent “…the best you have ever written me…” (WCP371). Sadly, the letter is missing from WCP - hopefully one day it will be found – but judging by Wallace’s reply it clearly included a lengthy piece on stereoscopic photography and an attack on pioneering photographer Antoine Claudet. The same year, Thomas moved from central London to Westbourne Grove. There followed a series of moves within Westbourne Grove Terrace - the cost of relocating the studio from Conduit Street estimated at £25. Debts followed Sims and he was chased by solicitors for back rent and shoddy building alterations at Conduit Street – this rankled on into the early 1860s. There was perhaps a period of stability when he was joined in business by his brother Edward Sims (1826-1908) for a few years, but Edward would leave to set up his own studio before later moving to Tunbridge Wells.

Things went from bad to worse and by summer 1869 Thomas and Fanny had moved to Crawley to live cheaply in the country. Thomas had given up photography and turned to portrait painting. Wallace, writing to his brother John, feared Sims would not make a living out of it and added:

The fact is [Fanny] is very badly off, having lost for years by that large house in Westbourne Grove, and after paying all her debts has not I fear more than £500 or £600 in the world (I have also lost £700 by their business). (WCP383)

Sim's business card (Ref: 1936.01.26)

Thomas then followed his brother Edward to Tunbridge Wells, but by 1882 he had returned to London where he rented a series of properties including 70 Lillie Road, West Brompton where he operated as a photographer. Sims made a wise commercial decision by producing some topical cabinet cards of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show - images of such events being popular – but he failed to market them properly. In a letter to Wallace in June 1887, Fanny wrote:

We go on in the same silly way, no persons of any note coming, a few of the poor, & the Cow Boys from the American Exhibition, we are obliged to do them all at half price, or we should not have them at all, I do not know what we are going to do, we shall see by March next but we must give notice at Xmas. (WCP400)

With business dire, Wallace continued to offer financial support and advice on where to sell Sims’s images and what subjects they should stop (“we do not think much of the flowers”) and what to take up:

“…the things to sell are something simple & domestic that everyone can understand & enjoy. Find a pretty, little laughing girl or boy, & take her or him in all sorts of positions & funny attitudes. A pretty kitten to make up little scenes with a few domestic utensils. Those kind of pictures would be more likely to sell than anything else.” (WCP1301)

The Final Years

Fanny died on 14 September 1893 and Thomas struggled on with his photography. By 1896 Wallace was concerned Sims was heading for the workhouse and attempted to find him employment, seeking advice from Raphael Meldola (FRS, British chemist and entomologist):

“My sister died about two years ago, & her husband, who was a photographer in a small business at West Brompton, has been sold up for rent, and is I fear in danger of absolute starvation or the workhouse. I feared it would be so as he is utterly unbusinesslike & depended wholly on my sister for all money matters. He is a good & experienced photographer… If such a thing as a photographer to a scientific man, or to any Institution where there is photographic work always going on, were required, I think he would suit…” (WCP4535)

Thomas moved back to Tunbridge Wells around 1900 and for the last ten years of Thomas’s life, Wallace supported him as best he could by sending money when asked. Sims wrote to Wallace on 1 March 1904:

“My monetary means are very short & L. Dodd has none in hand to give me -- in the last 14 months I have had £2 “ “ of him. My incomings are so small although the work so incessant that the rent will run on and that is where I feel the pinch at present. If you would advance me a little I would do my best by repaying by work or cash when the season advances.” (WCP1317)

First-generation photographers, like Sims, had no business model to follow and many failed to turn a profit and stopped trading. Some also became disillusioned with the direction of the discipline, especially the rise of mass market photography, and left the profession for that reason. Good money could be made by small and large businesses alike but Thomas – unlike his brother Edward – lacked the necessary entrepreneurial flair to succeed. He was essentially an experimenter, and would probably have been happier gaining recognition through articles, exhibitions and the fellowship of other pioneers.

Sims's main legacy is the corpus of written records and experimental samples he left behind. His images amply illustrate the work of an early photographer, but his notebooks, letters and memoir are a rare prize. The Wallace Correspondence Project is also a rare gift; as the letters help fill gaps in our knowledge about Thomas and provide a private window into the lives of him and Fanny. This post has only used a selection of the letters – there are others – why not have a deeper read?

[1] Talbot’s pocket book contains a faint pencil reference to Sims’s Times advert of 16 November 1853. More likely than not, Talbot would have passed the matter on to his solicitors. See British Library: Western Manuscripts, The Papers of William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) (1732-1952) (ADD MS88942) see File Add MS 88942/5/1/40, Pocket notebook (1853-1855)

Talbot’s solicitors set a watch on photographers who were thought to be infringing Talbot’s patent rights. Alfred Noble - a pupil of the College of Chemistry – was paid by the firm to watch a number of photographers. Posing as a customer, Noble sought to establish whether any were using the Ambrotype direct-positive process on glass. Noble compiled a list of 13 photographers in February 1855. Sims may have been one of them, he was certainly using the technique, but after Talbot’s Laroche defeat, his calotype patent was left to expire in February 1855. Incidentally, Alfred Noble had been one of Talbot’s witnesses in the case against Laroche the previous December (visiting Laroche to ask for lessons on the collodion process). British Library: Western Manuscripts, The Papers of William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) (1732-1952) (ADD MS88942) see File Add MS 88942/4/1/15.

[2] According to Kelly’s Directory, Sims is listed as a photographer at Conduit Street in 1856 and 1859. In 1857, there are no listings in Kelly’s or The Times. In 1858 he must have been there part of the year as he advertises in The Times in April and May. I think he must have sublet for part of the year as photographers Richey & Foskey are listed at his address. Note: Kelly’s isn’t always accurate, sometimes the information is months out of date.

Add new comment